The crisp October morning in Chicago brought an unexpected crowd to the Riverside estate sale. Among the curious buyers browsing through decades of accumulated treasures, antique dealer Sophia Martinez moved with practice efficiency. Her trained eye quickly separated valuable pieces from mere clutter as she navigated through the sprawling tutor style mansion.

The Williamson family had lived in this house for nearly a century before the last heir, elderly Margaret Williamson, passed away without children. Now, strangers rifled through their personal belongings. Each item tagged with a price that reduced a lifetime of memories to mere dollars and cents. In the mansion’s wood panled library, Sophia discovered a collection of framed photographs arranged on an antique mahogany desk.

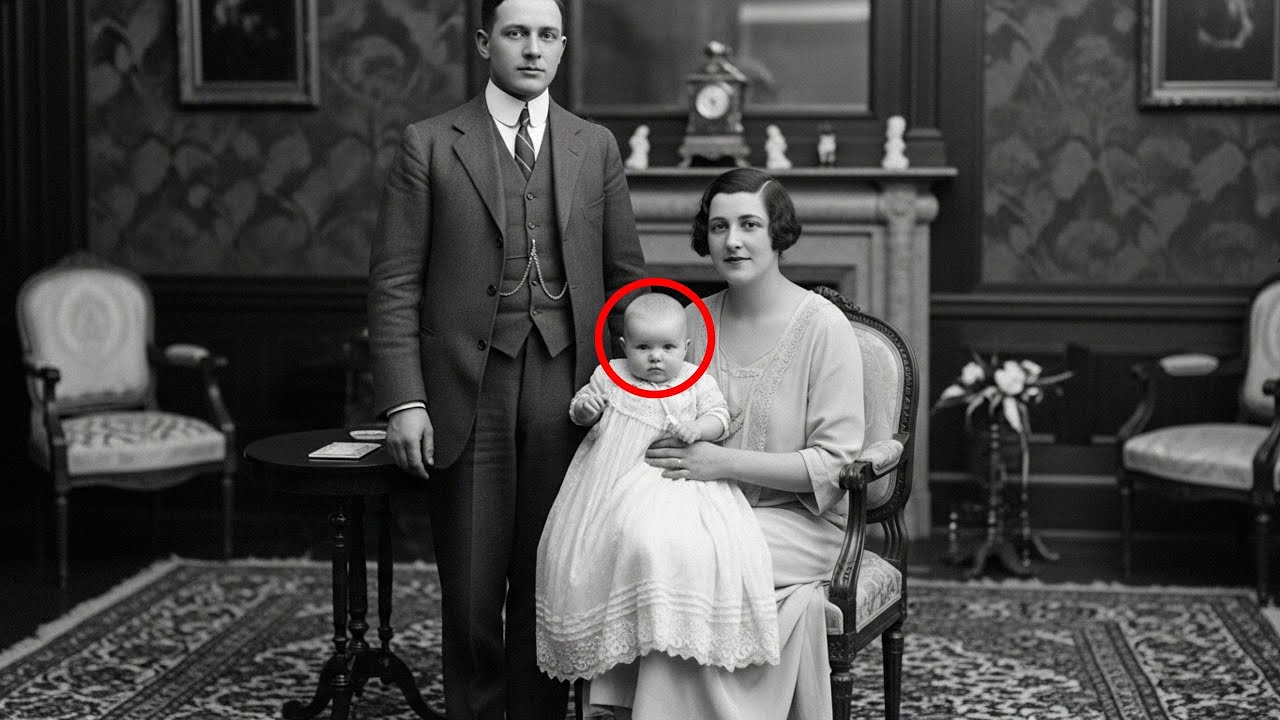

Most were typical family portraits from various decades, graduation photos, wedding pictures, holiday gatherings. But one particular frame caught her attention. Its ornate silver border tarnished with age. The photograph, clearly from the 1920s, based on the clothing and photographic style, showed a young couple posed in what appeared to be their living room.

The man wore a three-piece suit with a pocket watch chain, his hair sllicked back in the fashion of the era. The woman, dressed in a drop- waist dress, typical of the flapper period, sat gracefully beside him, a gentle smile playing on her lips. Between them, cradled in the woman’s arms, was an infant who couldn’t have been more than 6 months old.

The baby wore a long christening gown of delicate white lace, the kind wealthy families commissioned for special occasions. At first glance, the portrait embodied the prosperity and happiness of the roaring 20s. A successful couple with their precious child posed in their comfortable home. The lighting was professional, suggesting this was a formal portrait session rather than a casual family snapshot.

But as Sophia examined the photograph more closely, something about the baby’s expression made her pause. While the parents smiled warmly at the camera, radiating contentment and pride, the infant’s eyes held something entirely different. Even at such a young age, there was an unmistakable intensity in that tiny face. Not the blank innocent gaze typical of babies, but something that seemed almost aware, almost fearful.

Sophia purchased the photograph for $25. Unable to shake the feeling that those small eyes were trying to tell her something important. Back in her antique shop in Lincoln Park, Sophia carefully removed the photograph from its frame to examine it more thoroughly. Her years of experience had taught her that the most valuable information about old photographs often lay hidden on the back.

Photographers stamps, dates, names, or notes that provided crucial context. The back of the photograph revealed exactly what she had hoped to find, an embossed stamp reading Henrik Kowalsski Photography Studio, Chicago, Illinois, along with a date written in elegant script, October 15th, 1920. Below that, in different handwriting were three names, Robert, Catherine, and baby Thomas Williamson.

Sophia’s pulse quickened. She recognized the Kowalsski name. Henrik Kowalsski had been one of Chicago’s most prestigious portrait photographers during the 1920s, known for capturing the wealthy elite of the city. His work was highly sought after by collectors, but more importantly, Kowalsski had been famous for his meticulous recordkeeping.

If his studio archives still existed, they might contain valuable information about this particular session. She spent the next 2 hours searching online databases and historical records. What she discovered made the photograph even more intriguing. Robert Williamson had been a successful banker in 1920, part of Chicago’s financial elite.

Catherine Williamson, Nay Hartford, came from old money. Her family had made their fortune in railroad investments during the late 1800s. But it was information about baby Thomas that stopped Sophia cold. According to a Chicago Tribune obituary she found in the newspaper archives, Thomas Williamson had died in November 1920, just one month after this photograph was taken.

The cause of death was listed as sudden infant death syndrome, though the medical understanding of Sids in 1920 was primitive at best. Sophia stared at the photograph again, focusing on the baby’s eyes. Now that she knew Thomas would be dead within weeks of this portrait being taken, his expression seemed even more haunting.

Was it possible that somehow in that mysterious way that sometimes occurred with old photographs, the camera had captured something that the human eye couldn’t see? She reached for her phone to call Dr. Elizabeth Chen, a photography historian at Northwestern University who specialized in early 20th century portraiture. If anyone could help her understand the technical aspects of what she was seeing, it would be Dr. Chen.

I have a 1920 Kowalsski portrait that’s unusual, Sophia explained. The baby’s expression doesn’t match the parents mood at all. It’s almost as if the child is seeing something the adults can’t. Bring it in tomorrow morning, Dr. Chen replied, her voice immediately interested. Kowalsski was known for capturing things other photographers missed.

His portraits often revealed more than his subjects intended to show. Dr. Elizabeth Chen’s office at Northwestern University resembled a museum of photographic history. Vintage cameras from different eras lined the shelves and the walls displayed examples of significant portrait photography spanning nearly two centuries.

When Sophia arrived the following morning, Dr. Chen was already preparing her examination equipment. Henrik Kowalsski. Dr. Chen mused as she carefully placed the photograph under her specialized lighting. He was an interesting figure in Chicago’s photography scene. Immigrated from Poland in 1910, built a reputation for portraits that seemed to capture people’s inner essence rather than just their appearance.

Through her magnifying equipment, Dr. Chen studied every detail of the image. The technical quality is exceptional, even by Kowalsski’s standards. Look at the depth of field, the way he’s captured the texture of the mother’s dress, the intricate details of the baby’s christening gown. Sophia watched as Dr.

Chen focused intently on the baby’s face. What’s unusual about the infant’s expression? Several things. First, babies this young, probably 4 to 6 months old, typically have very limited facial expressions. They might smile reflexively, cry, or sleep. But this child appears to be focusing on something specific outside the camera’s range. Dr.

Chen adjusted her equipment to get a clearer view. Look at the direction of his gaze. He’s not looking at his parents, not at the photographer, but towards something to the left of the camera setup. Could it be a sound that caught his attention? Possibly, but notice his facial expression. This isn’t curiosity or startle response.

If I had to describe it, I’d say it looks like weariness, even fear. Dr. Chen continued her examination, paying special attention to the lighting and shadows in the photograph. There’s something else interesting here. Kowalsski was famous for his use of natural light. But in this portrait, there are multiple light sources.

See these shadow patterns? They suggest there was strong lighting coming from that same direction the baby is looking toward. What kind of lighting? Hard to say definitively, but it’s not consistent with the soft natural light Kowalsski typically preferred. It’s almost as if something bright, perhaps reflected light or an additional lamp, was positioned in that area during the shoot.

Doctor Chen leaned back in her chair, removing her glasses in a gesture Sophia was beginning to recognize as significant. Sophia, in my experience, when babies this young show such a specific focused expression, they’re usually reacting to something immediate in their environment. The question is, what was in that room that we can’t see in the photograph? The baby died a month later, Sophia revealed quietly.

Sudden infant death syndrome, according to the records. Doctor Chen’s expression grew more serious. That changes things. In 1920, Sids wasn’t well understood, and many infant deaths that might have had other causes were attributed to it. Combined with this child’s expression, she paused, studying the photograph again.

I think we need to research this family more thoroughly. Sophia spent the following days immersed in research at the Chicago History Museum. The Williamson family records painted a picture of typical wealthy Chicagoans of the 1920s. charity events, business dealings, society page mentions. But as she dug deeper into newspaper archives and public records, a more complex story began to emerge.

Robert Williamson, she discovered, had not been merely a banker. He had been involved in several controversial financial deals during 1919 and 1920, including investments that were later investigated for fraud. While never formally charged, his name had appeared in connection with schemes that had cost several families their life savings.

More troubling were the personal details she uncovered. Katherine Williamson had been hospitalized twice during 1920 for what the medical records euphemistically called nervous exhaustion, a common diagnosis for women suffering from what would now be recognized as severe depression or anxiety. But it was a small item in the Chicago Tribune Society section from November 1920 that made Sophia’s blood run cold following the tragic loss of their infant son Thomas. Mr. and Mrs.

Robert Williamson have announced their intention to travel abroad indefinitely. Mrs. Williamson’s physician has recommended a change of climate for her health. Sophia found more clues in the Cook County property records. The Williamsons had sold their house on North Lakeshore Drive in December 1920, just 2 months after the portrait was taken, and one month after Baby Thomas’s death, the sale was handled quickly and quietly with the house selling for significantly less than its assessed value.

At the Chicago Public Libraryies genealogy section, Sophia discovered something even more disturbing. Thomas Williamson had not been the couple’s first child to die young. Catherine had given birth to a daughter Mary in 1918. According to the death certificate, Mary had died at 8 months old. Also attributed to sudden infant death syndrome.

Two babies, both dead before their first birthdays. Both deaths attributed to the same mysterious cause that doctors in 1920 barely understood. Sophia stared at the photograph again, focusing on baby Thomas’s worried expression. Had this child somehow sensed that he was in danger? Her research led her to one more crucial discovery.

The Williamson’s house on North Lakeshore Drive was still standing. It had been converted into luxury condominiums in the 1980s, but the building’s original structure remained largely intact. The current owner of what had been the Williamson’s unit was Dr. Amanda Foster, a pediatrician who had purchased the condo specifically because of its historical significance. Sophia called Dr.

Foster, explaining her research into the photograph and the Williamson family’s tragic history. I’d love to see where this portrait was taken. Sophia said, “Sometimes seeing the actual space can provide clues about what was happening when a photograph was made.” Of course, Dr. Foster replied, “Though I should warn you, there are some unusual things about this apartment that might interest you given what you’re investigating.

” Dr. Amanda Foster’s condominium occupied the entire third floor of the elegant limestone building on North Lake Shore Drive. As she led Sophia through the renovated space, it was easy to imagine how it had looked in 1920. Spacious rooms with high ceilings, large windows overlooking Lake Michigan, the kind of home that proclaimed its owner’s success and social standing.

The living room where your photograph was likely taken is through here. Doctor Foster said, guiding Sophia into a beautifully appointed room with original hardwood floors and restored crown molding. I’ve tried to maintain the historical character while updating it for modern living. Sophia pulled out the photograph, comparing it to the current space.

Despite the modern furniture and updated lighting, she could recognize the room’s basic structure, the placement of windows, the architectural details, even the general positioning where the Williamsons would have posed for their portrait. When I bought this place 15 years ago, I researched its history. Dr. Foster continued. The Williamson story was part of what drew me to it.

Actually, as a pediatrician, I was intrigued by the mystery of their children’s deaths. Mystery? Dr. Hump. Foster gestured for Sophia to sit down, her expression growing serious. I’ve seen thousands of cases of infant mortality in my career, and while SIDS does occur, two cases in the same family within 2 years is extremely unusual. modern medicine would have investigated much more thoroughly.

She walked to a bookshelf and retrieved a folder. After I moved in, I found some things the previous owners had left behind. Documents, photographs, even some personal items that had been stored in the basement for decades. Sophia’s heart raced as Dr. Foster opened the folder. Inside were several items that clearly dated to the Williamson era.

Household bills, personal correspondence, and most remarkably, a letter from Catherine Williamson to her sister, dated November 20th, 1920, just 5 days after baby Thomas’s death. May I? Sophia asked, reaching for the letter. The handwriting was shaky, clearly written by someone under extreme emotional distress. Dearest Margaret, I cannot bear to stay in this house another day.

Thomas is gone just like Mary and I know in my heart that Robert I cannot write the words but you know what I suspect. The doctor says it was the same condition that took Mary but I have seen how Robert looks at the children when he thinks no one is watching. There is something cold in his eyes. Something that frightens me.

I found the bottle of ladum hidden in his study far more than any person would need for occasional pain. And the night Thomas died, Robert had been alone with him for over an hour before calling for help. When I touched my baby’s skin, it was so cold, Margaret. So very cold. Sophia’s hands trembled as she finished reading. She looked up at Dr.

Foster, who nodded grimly. “There’s more,” Dr. Foster said quietly. “I think you should see the room that was the nursery.” Dr. Foster led Sophia down a hallway to what had been converted into her home office. “This was the nursery in 1920. When I renovated, I discovered something behind the original wallpaper that the previous owners had never removed.

” She pointed to a section of wall where the historical wallpaper had been carefully preserved under glass. Look closely at the pattern. Sophia examined the delicate floral wallpaper, typical of the period. But as she studied it more carefully, she noticed something unusual. In several places, the pattern was interrupted by small dark stains that looked almost like fingerprints.

Dr. Foster confirmed. tiny fingerprints pressed into the wallpaper at about the height where a crib would have been placed. And they’re not alone. She led Sophia to another section of the preserved wallpaper where the stains were different, larger, more irregular. These tested positive for Ldam when I had them analyzed out of curiosity.

Sophia stared at the evidence, her mind reeling. You think Robert Williamson was drugging his children? I think Robert Williamson was systematically poisoning his children with ldinum. and Catherine suspected it but couldn’t prove it. Ldinum was readily available in 1920, often used for everything from headaches to insomnia.

A banker like Robert would have had easy access to it, and the symptoms of ldinum poisoning in infants could easily be mistaken for acids. Dr. Foster walked to her desk and retrieved another document. I also found this, a partial diary entry that Catherine apparently hid behind a loose floorboard. The diary entry written in Catherine’s increasingly desperate handwriting painted a horrifying picture. October 10th, 1920.

Thomas has been so listless lately, sleeping far more than a healthy baby should. When I mentioned this to Robert, he became angry, saying I was being an overprotective mother, just as I had been with Mary. But I watch him when he thinks I’m not looking. I’ve seen him give Thomas what he claims is medicine, but the baby always becomes drowsy afterward.

I found the small brown bottle in Robert’s study again, the same type that was there when Mary was sick. He says it’s for his back pain, but I’ve never seen him take any. And there are marks on the bottles. Tiny scratches that look like someone has been measuring doses. Tonight, I’m going to watch more carefully. I’m going to protect Thomas, even if it means the entry ended abruptly, the handwriting trailing off as if Catherine had been interrupted.

Sophia looked back at the photograph, understanding now why baby Thomas’s eyes held such weariness. He was looking at his father during the portrait session. That would be my assessment, Dr. Foster agreed. Babies that young are incredibly sensitive to danger. If Robert Williamson had been systematically poisoning Thomas, the child would have learned to associate his father’s presence with feeling sick, with pain.

That expression in the photograph isn’t random. It’s a baby’s instinctive recognition of threat. Armed with this new understanding, Sophia returned to her research with renewed urgency. She needed to find Henrik Kowalsski’s studio records, hoping they might contain additional details about the portrait session that could confirm their suspicions.

After several phone calls and emails, she discovered that Kowalsski’s archives had been donated to the Chicago Photography Archives at Columbia College after his death in 1965. The archavist, Dr. Marcus Webb agreed to meet with Sophia to examine any records related to the Williamson portrait. Kowalsski was incredibly detailed in his recordeping, Dr.

Webb explained as they descended into the climate controlled basement where the archives were stored. He documented not just the technical aspects of each shoot, but often included personal observations about his subjects. They located the 1920 ledger, and Dr. Webb carefully turned to the October entries. There in Kowalsski’s precise handwriting was the entry for October 15th, 1920.

Mr. and Mrs. Robert Williamson with infant son Thomas. Commission formal family portrait for holiday cards. Payment $50 in advance. Technical notes. Natural lighting from east windows supplemented with reflector. Mrs. Williamson very nervous throughout session. Frequently checking on baby. Mr.

Williamson impatient wanted to complete session quickly. Personal observations. Unusual family dynamic. Baby appeared distressed whenever father approached. Mrs. W. Very protective would not allow husband to hold child during poses. Infant healthy appearing but seemed unusually alert, shocked, wary for age. Recommended they reschedule when baby more settled, but Mr. W insisted on proceeding.

Final note. During final exposures, baby became agitated when father moved closer for group pose. expression captured shows infants clear distress. Mrs. W requested I not include certain poses in final selection. Sophia felt a chill run down her spine. Even the photographer had noticed the strange family dynamics and baby Thomas’s fear of his father.

But there was more. Dr. Webb found a folder of correspondence related to the Williamson session. Inside was a letter from Katherine Williamson to Kowalsski dated November 25th, 1920, 10 days after Thomas’s death. Dear Mr. Kowalsski, I am writing to request all photographs and negatives from our October session.

My husband has asked me to retrieve them due to our son’s recent passing. However, I must ask you a personal favor. If you observed anything unusual during our session, anything that concerned you about my family’s welfare, please document it and keep those records safe. I fear there may come a time when such observations become important.

I am enclosing payment for an additional set of prints to be held in your personal files. Please do not mention this to my husband. Sincerely, Mrs. Catherine Williamson. P.S. My baby’s eyes in that final photograph. You captured something important. Please preserve it. Sophia realized that what she had uncovered was potentially evidence of century old murders.

Despite the passage of time, she felt a moral obligation to document her findings properly. She contacted Detective Maria Santos of the Chicago Police Department’s cold case unit, explaining that she had discovered evidence related to suspicious infant deaths from 1920. Detective Santos, a seasoned investigator with 15 years of experience, was intrigued enough to meet with Sophia at the antique shop.

As Sophia laid out all the evidence, the photograph, Catherine’s letters, Dr. Foster’s discoveries, and Kowalsski’s records, Detective Santos listened with growing interest. “Obviously, we can’t prosecute a case from 1920,” Detective Santos said. “But from an investigative standpoint, this is fascinating. The pattern you’ve identified is consistent with what we now know about family annihilators, people who systematically kill family members, often for financial reasons.

” She studied the photograph carefully. Infanticide cases from that era were rarely investigated thoroughly, especially when the perpetrator was a wealthy, respected member of the community, and ldinum poisoning would have been almost impossible to detect with 1920s medical knowledge. Detective Santos pulled out her laptop and began searching modern databases.

Let me see what I can find about Robert Williamson’s later life. After several minutes of searching, she found records that made the case even more compelling. Robert Williamson remarried in 1925 to a wealthy widow named Helen Morrison. She had two young children from her previous marriage, a son and a daughter.

Sophia’s heart sank, sensing what was coming next. Both children died within 2 years of the marriage. The son in 1926, age 6, attributed to pneumonia. The daughter in 1927, age 4, from what was called wasting sickness. Helen Morrison Williamson died in 1928, apparently from grief and declining health. He did it again, Sophia whispered.

It certainly appears that way. By 1930, Robert Williamson had inherited substantial wealth from his second wife and had moved to California, where he lived comfortably until his death in 1954. Never remarried, no more children. Detective Santos closed her laptop. What you’ve uncovered here is evidence of a serial killer who used his social position and the medical limitations of his era to murder multiple family members, probably for financial gain.

Robert Williamson eliminated his own children and stepchildren and likely contributed to his wife’s deaths through psychological abuse. She looked at the photograph again, focusing on baby Thomas’s fearful expression. This child knew he was in danger. Somehow that camera captured his recognition of a threat that the adults around him either couldn’t see or chose to ignore.

As word of Sophia’s discovery spread through academic and historical circles, she received an unexpected phone call from Dr. Patricia Williamson, a retired psychiatrist living in Portland, Oregon. Dr. Williamson explained that she was the great great niece of Catherine Williamson, and had been researching her family’s history for years.

I’ve been trying to understand what happened to Catherine after she left Chicago in 1920. Dr. Williamson said, “Your research may have finally provided the answers I’ve been looking for.” They arranged to meet when Dr. Williamson flew to Chicago the following week. She brought with her a collection of family documents that had been passed down through Catherine’s sister’s family, items that Catherine had sent to her sister Margaret over the years.

The most significant discovery was Catherine’s complete diary, which she had apparently mailed to Margaret in pieces between 1920 and 1925. The complete diary told a harrowing story of a woman who had slowly realized that her husband was a murderer, but had been trapped by the social and legal constraints of her era.

The entry for October 15th, 1920, the day of the portrait session, was particularly revealing. Today, we had our photograph taken. I insisted that Thomas be included, though Robert was reluctant. He said the baby would spoil the formal nature of the portrait. But I wanted a record of our family while Thomas is still with us.

I have such fears about his health lately. During the session, I watched Robert’s face when he looked at Thomas. The same expression I remember from when Mary was sick, a kind of cold calculation, as if he were studying a problem to be solved rather than looking at his own child. The photographer, Mr. Roar. Kowalsski was very kind and patient.

He seemed to notice that Thomas became upset whenever Robert came near. When I asked him to take several poses with just Thomas and myself, Robert became angry, but Mr. Kowalsski supported my request. I pray that Thomas will grow stronger. But I fear I fear that Robert sees our children as obstacles to something he wants more.

I found papers in his study related to life insurance policies, and there are financial documents I don’t understand. Sometimes I catch him looking at me with the same cold expression he gives the children. The diary continued through the weeks following Thomas’s death, documenting Catherine’s growing certainty that Robert had murdered their son.

November 20th, 1920. I confronted Robert tonight about the ldinum. He became furious, saying I was having another one of my nervous episodes, but I showed him the bottle I found, the one with the residue that smells so sweet and sickly. He claimed it was old medicine left over from when the doctor treated my headaches, but I know he’s lying.

I cannot stay in this house. I cannot pretend to grieve with the man who killed my babies. Tomorrow, I will take what money I can access and go to Margaret. Robert can have his wealth and his reputation. I only want to be free of him before he decides that I too have become an obstacle. 6 months after Sophia’s initial discovery, the Williamson case had become a subject of academic study and historical fascination.

The portrait that had seemed so innocuous at first glance was now recognized as one of the most significant pieces of criminal evidence from the early 20th century. Dr. Chen organized a symposium at Northwestern University titled Photography as Historical Evidence, the case of the 1920 Williamson portrait. Scholars from across the country attended to examine how modern investigative techniques could reveal truths hidden in historical photographs.

Sophia stood before an audience of historians, criminologists, and photography experts. The enlarged portrait displayed prominently behind her. Baby Thomas’s fearful eyes seemed to watch over the proceedings, finally receiving the attention and understanding he had been denied in life. This photograph teaches us that truth has a way of preserving itself.

Even when powerful people try to bury it, Sophia concluded her presentation. Baby Thomas Williamson couldn’t speak, couldn’t testify, couldn’t protect himself, but his eyes told a story that survived for over a century, waiting for someone to recognize what they were seeing. In the audience, Dr. Patricia Williamson wiped away tears.

After the presentation, she approached Sophia with one final piece of Catherine’s story. Catherine lived until 1965, she said quietly. She never remarried, never had more children. She spent her life working with organizations that helped abused women and children, though she never spoke publicly about her own experiences.

She kept that photograph of Thomas until the day she died, along with all her evidence against Robert. Why didn’t she ever go to the police? Sophia asked different times. a woman’s word against a respected banker, especially when accusing him of murdering his own children. She knew no one would believe her. But she documented everything, hoping that someday someone would understand. Dr.

Patricia Williamson handed Sophia a final envelope, Catherine’s last letter, written just before she died. She asked that it be opened only if someone ever discovered the truth about her children. With trembling hands, Sophia opened the envelope and read Catherine’s final words. to whoever finds this truth.

My babies were murdered by their father, Robert Williamson, and I was powerless to save them. I have carried this secret for 45 years, hoping that someday justice would find a way. If you are reading this, then Thomas’s eyes finally spoke their truth. Please remember that he was loved, that he was innocent, and that his brief life mattered.

Please remember that evil sometimes wears a respectable face, but truth has a way of surviving even the most powerful lies. Thank you for seeing what I saw in that photograph. Thank you for listening to my baby’s silent testimony. May this knowledge help protect other children from suffering as mine did. As the symposium ended and people began to leave, Sophia remained seated, looking up at the enlarged portrait.

Baby Thomas’s eyes, no longer mysterious, had finally told their story. The photograph that had once shown a happy family now stood as a testament to the power of truth and the importance of believing those who cannot speak for themselves. The portrait found its permanent home in the Chicago History Museum, displayed with the full story of the Williamson family tragedy.

Visitors often remarked on the baby’s unusual expression, and now finally they could understand what those young eyes had been trying to say all along.